The History Guy:

The Mexican-

The U.S.-

The Mexican-

MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR CAUSES OF CONFLICT:

The war between the United States and Mexico had two basic causes. First, the desire of the U.S. to expand across the North American continent to the Pacific Ocean caused conflict with all of its neighbors; from the British in Canada and Oregon to the Mexicans in the southwest and, of course, with the Native Americans. Ever since President Jefferson’s acquisition of the Louisiana Territory in 1803, Americans migrated westward in ever increasing numbers, often into lands not belonging to the United States. By the time President Polk came to office in 1845, an idea called “Manifest Destiny” had taken root among the American people, and the new occupant of the White House was a firm believer in the idea of expansion. The belief that the U.S. basically had a God-

The second basic cause of the war was the Texas War of Independence and the subsequent annexation of that area to the United States. Not all American westward migration was unwelcome. In the 1820’s and 1830’s, Mexico, newly independent from Spain, needed settlers in the underpopulated northern parts of the country. An invitation was issued for people who would take an oath of allegiance to Mexico and convert to Catholicism, the state religion. Thousands of Americans took up the offer and moved, often with slaves, to the Mexican province of Texas. Soon however, many of the new “Texicans” or “Texians” were unhappy with the way the government in Mexico City tried to run the province. In 1835, Texas revolted, and after several bloody battles, the Mexican President, Santa Anna, was forced to sign the Treaty of Velasco in 1836 . This treaty gave Texas its independence, but many Mexicans refused to accept the legality of this document, as Santa Anna was a prisoner of the Texans at the time. The Republic of Texas and Mexico continued to engage in border fights and many people in the United States openly sympathized with the U.S.-

Mexico of course did not like the idea of its breakaway province becoming an American state, and the undefined and contested border now became a major international issue. Texas, and now the United States, claimed the border at the Rio Grande River. Mexico claimed territory as far north as the Nueces River. Both nations sent troops to enforce the competing claims, and a tense standoff ensued. On April 25, 1846, a clash occurred between Mexican and American troops on soil claimed by both countries. The war had begun.

DESCRIPTION OF THE MEXICAN-

The Mexican-

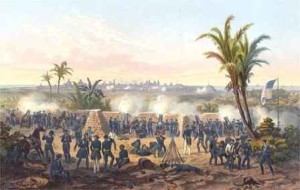

After the beginning of hostilities, the U.S. military embarked on a three-

On March 9, 1847, General Scott landed with an army of 12,000 men on the beaches near Veracruz, Mexico’s most important eastern port city. From this point, from March to August, Scott and Santa Anna fought a series of bloody, hard-

On February 2, 1848, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, later to be ratified by both the U.S. and Mexican Congresses. The treaty called for the annexation of the northern portions of Mexico to the United States. In return, the U.S. agreed to pay $15 million to Mexico as compensation for the seized territory. The bravery of the individual Mexican soldier goes a long way in explaining the difficulty the U.S. had in prosecuting the war. Mexican military leadership was often lacking, at least when compared to the American leadership. And in many of the battles, the superior cannon of the U.S. artillery divisions and the innovative tactics of their officers turned the tide against the Mexicans. The war cost the United States over $100 million, and ended the lives of 13,780 U.S. military personnel. America had defeated its weaker and somewhat disorganized southern neighbor, but not without paying a terrible price.

CONSEQUENCES OF THE MEXICAN-

1. The United States acquired the northern half of Mexico. This area later became the U.S. states of California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Utah.

2. President Santa Anna lost power in Mexico following the war.

3. U.S. General Zachary “Old Rough and Ready” Taylor used his fame as a war hero to win the Presidency in 1848. A true irony is that President Polk, a Democrat, pushed for the war that led to Taylor, a Whig, winning the White House.

4. Relations between the United States and Mexico remained tense for many decades to come, with several military encounters along the border.

5. For the United States, this war provided a training-

UNIQUE FACTS OR TRENDS OF THE MEXICAN-

1. This war featured the first major amphibious landing by U.S. forces in history.

2. The defeat of Mexico was the first time a foreign enemy force occupied the capital of the nation. The French would also occupy Mexico City in the 1860’s.

3. Despite early popularity at home, the war was marked by the growth of a loud anti-

4. One interesting aspect of the war involves the fate of U.S. Army deserters of Irish origin who joined the Mexican Army as the Batallón San Patricio (Saint Patrick’s Battalion). This group of Catholic Irish immigrants rebelled at the abusive treatment by Protestant, American-

5. In Mexico, a special day is remembered to celebrate the bravery of the teenaged military cadets at the military academy at Chapultepec Castle, which was attacked by Scott’s army on September 13, 1847. “Dia de Los Niños Heroes de Chapultepec” (“day of the boy heroes of Chapultepec), is commemorated every year on the anniversary of the battle.

Ordered to retreat by their Commandant, these young cadets joined the fight-

CASUALTY FIGURES OF THE MEXICAN-

United States Casualties–

Mexico Casualties–

DATES OF THE MEXICAN-

THE MEXICAN-

THE MEXICAN-

ALTERNATE NAMES FOR THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR:

U.S. Names: U.S.-

Mexican Names: primera intervención estadounidense en México (United States’ First Intervention in Mexico), invasión estadounidense a México(United States’ Invasion of Mexico), and guerra del 47 (The War of 1847).

Predecessor Conflicts: (Prior related conflicts )

The Texas War of Independence (1835-

Texas-

U.S. Seizure of Monterey (1842)

Concurrent Conflicts: (Related conflicts occurring at the same time)

The Bear Flag Revolt in California (1846)

Apache War in New Mexico (1847)

Taos Rebellion (1847)

Sources and links on the Mexican-

1. Kohn, George C. Dictionary of Wars. New York: Facts On File Publications. 1986.

2. Eisenhower, John S.D. .So Far From God: The U.S. War With Mexico 1846-

3. Winders, Richard Bruce. Mr. Polk’s Army. Texas A&M, 1997.

4. Frazier, Donald S., ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War: Nineteenth Century Expansionism and Conflict. Macmillan Library Reference, 1998.

U.S. Historical Flag courtesy of: FOTW Flags Of The World website at http://fotw.digibel.be/flags/

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.